A lot of what we do here at Molded Dimensions Inc. is technical, precise, and extremely detailed. This blog post breaks down compression and shape factor for molded rubber and urethane mechanical components in a way that can be understood by engineers and lay persons. These basic principles described here are useful when applied by designers throughout the part design process.

Compression

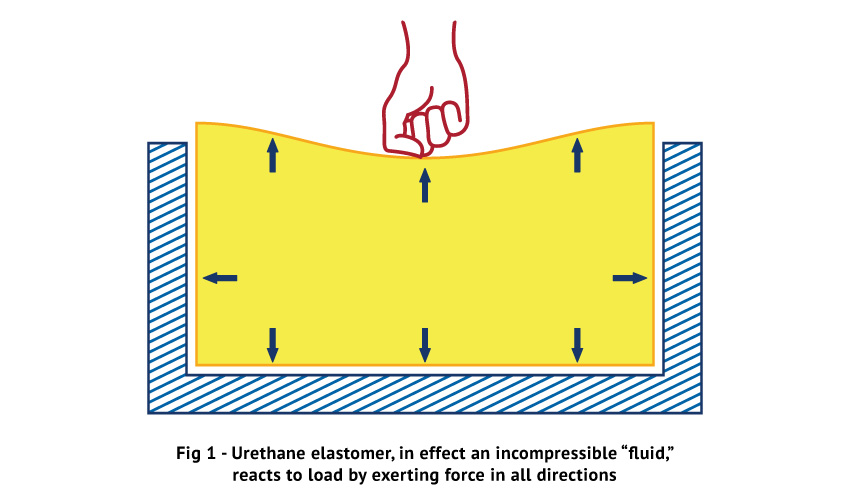

When a load is applied to an elastomer, it “flows” in accordance with the force exerted on it and within the limits provided by the mass of the material itself or by the dimensions of its container. In rubber technology this is called compression. Although this term is correct in the framework of normal rubber usage, it may be misleading to the engineer. It does not mean that the elastomer will undergo a change in volume under pressure. Rather, it means the elastomer will deflect, or undergo a change in shape. This distinction is important. An elastomer is an incompressible fluid, capable of changing its shape to the limit of its strength under load. It will react to a load placed upon it by tending to exert force uniformly in all directions. Even though the elastomer is changed in shape under load, it is compelled by the characteristic of elasticity to return to its original shape once the load is removed.

Compressive Strain

Compressive strain can be considered to be extensions of tensile strain, which are continuous through the origin. However, the compressive samples must be free to move, ie, the faced must be lubricated. Generally, rubber in compression is bonded to the surface or surface friction restricts movement. Compression curves are usually smooth and do not exhibit the “S” shape usually found in tensile tests. Compressive strain is limited to less than 100% and, therefore, the curve becomes asymptotic to the 100% line.

Shape Factor

While the ability to deform under compressive stress and then recover is a characteristic property of elastomers, other factors, notably the shape of the part, affect the way an elastomer deforms in compression. To illustrate, consider two blocks cut from the same piece of rubber. One is a cylinder with the proportions of an ice-hockey puck, the other is a block of the same height and cross-sectional area, but rectangular in shape. If equal weights are placed on the blocks, subjecting them to the same compressive stress, the rectangular block will deflect more than the cylinder. Since the blocks will not change in volume, the reduction in height is caused by the freedom of the sides to bulge. The rectangular block deflects more than the cylindrical one because the sides of the rectangular block provide a greater area free to bulge.

The designer of elastomeric parts allows for this behavior by using a concept called shape factor. Shape factor describes the role of the shape in determining how a part with parallel load faces will behave under compressive forces.

The concept of shape factor is useful for the design engineer. If the elastomeric part does not deflect enough to do its job, the designer can reduce the shape factor by increasing the thickness of the pad. In reality, he does no more than increase the area free to expand under load. If the pad deflects too much, he may decrease the area free to expand he may increase the hardness of the elastomer.