There are two types of abrasion – sliding and impingement. Sliding is the passing of an adjacent surface across the rubber surface. Impingement is wearing of the rubber exemplified by sand particles hitting the surface. Most wear in actual service occurs as a combination of both sliding and impingement.

When sliding, localized friction forces can impose high energy levels on the rubber. Abrasion and wear takes place when the rubber cannot withstand these forces.

Impingement by particles occurs in applications such as chutes, rebound plates and sandblast hose. Elastomers can yield easily and distribute stresses imposed by particle impingement. A sandblast test shows that with a 90 degree impingement angle, soft resilient rubber is more abrasion resistant that steel or cast iron. However, not just any elastomer can be used. Under this same condition, a tough tire tread will wear out more rapidly that a soft elastomer. The angle of particle impingement has a significant effect on which material should be used. The angle of particle impingement has a significant effect on which material should be used. As the angle decreased below 90 degree, the superiority of elastomers over metals declines and disappears.

Laboratory abrasion tests are difficult to correlate with end-use applications. Measurement of properties can be helpful in selection of materials, but do not compare to rates in actual service, which can be thousands of times greater with regard to velocities and temperatures.

There are at least 25 laboratory abrasion test devises, an indication that this type of test is difficult to correlate with service performance. The most widely recognized test device in the rubber industry is the National Bureau of Standards Abrader, a slinging type abrader. The NBS Abrader uses a constant velocity, under a fixed load using a specified abrasive grit.

It does not tell how a compound performs under widely varying conditions, nor does it tell anything about cut resistance, chunking, or flat spotting.

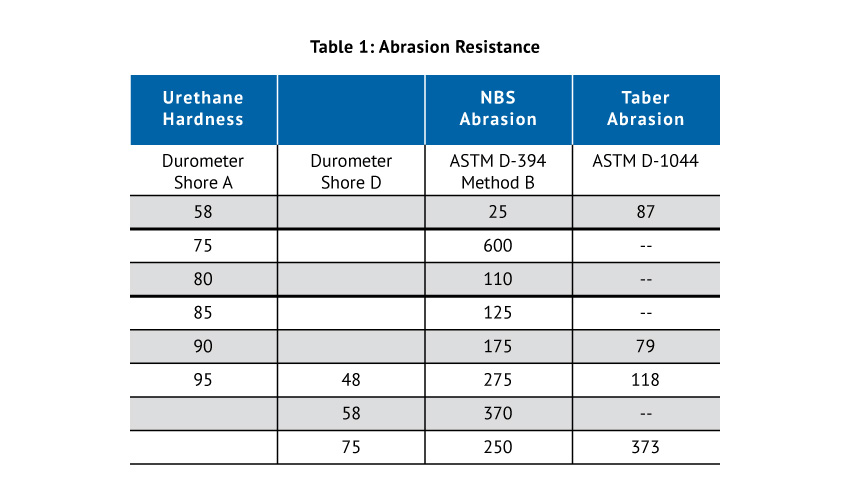

The abrasion resistance of vulcanizated of urethane, as measured on two laboratory tests, the National Bureau of Standards test and the Taber Abrader, are shown in Table I.

Note that these two tests give different values. The differences in performance of vulcanizates of urethane can be explained however. The NBS test simulates a very harsh service. In this case, the hardest vulcanizates hold up best. The Taber test is much less severe. In this case, the hardest vulcanizates hold up best. The Taber test is much less severe. Softer compounds perform better than the harder ones because they are more resilient and “give” under load.

The resistance to sliding abrasion increases with increasing hardness for the NBS test. The unusually high NBS Index for the 75A durometer vulcanizate is probably due to lubrication of the abrasive wheel by the plasticizer used in the compound.

As the hardness of urethane increases, NBS values increases for non-plasticized compounds.

In spite of the difficulties in obtaining meaningful laboratory abrasion test values, urethane is considered to have excellent sliding abrasion resistance and has performed well in many applications where wear is a problem. Urethane has outworn conventional rubber and plastics often by a factor of as much as 8 to 1.

Table I

|

Urethane Hardness |

NBS Abrasion |

Taber Abrasion |

|

|

Durometer Shore A |

Durometer Shore D |

ASTM D-394 Method B |

ASTM D-1044 |

|

58 |

|

25 |

87 |

|

75 |

|

600 |

— |

|

80 |

|

110 |

— |

|

85 |

|

125 |

— |

|

90 |

|

175 |

79 |

|

95 |

48 |

275 |

118 |

|

|

58 |

370 |

— |

|

|

75 |

250 |

373 |